The ‘Ole Ball Games: what did people play before soccer?

While soccer is a relatively modern sport, its origins can be traced back to much earlier times. Indigenous cultures in North and Central America, as well as ancient China, had their own unique style of games that feel familiar. These ancient games show the enduring appeal of sport, both social and spiritual, across cultures and time periods.

蹴鞠

CUJU

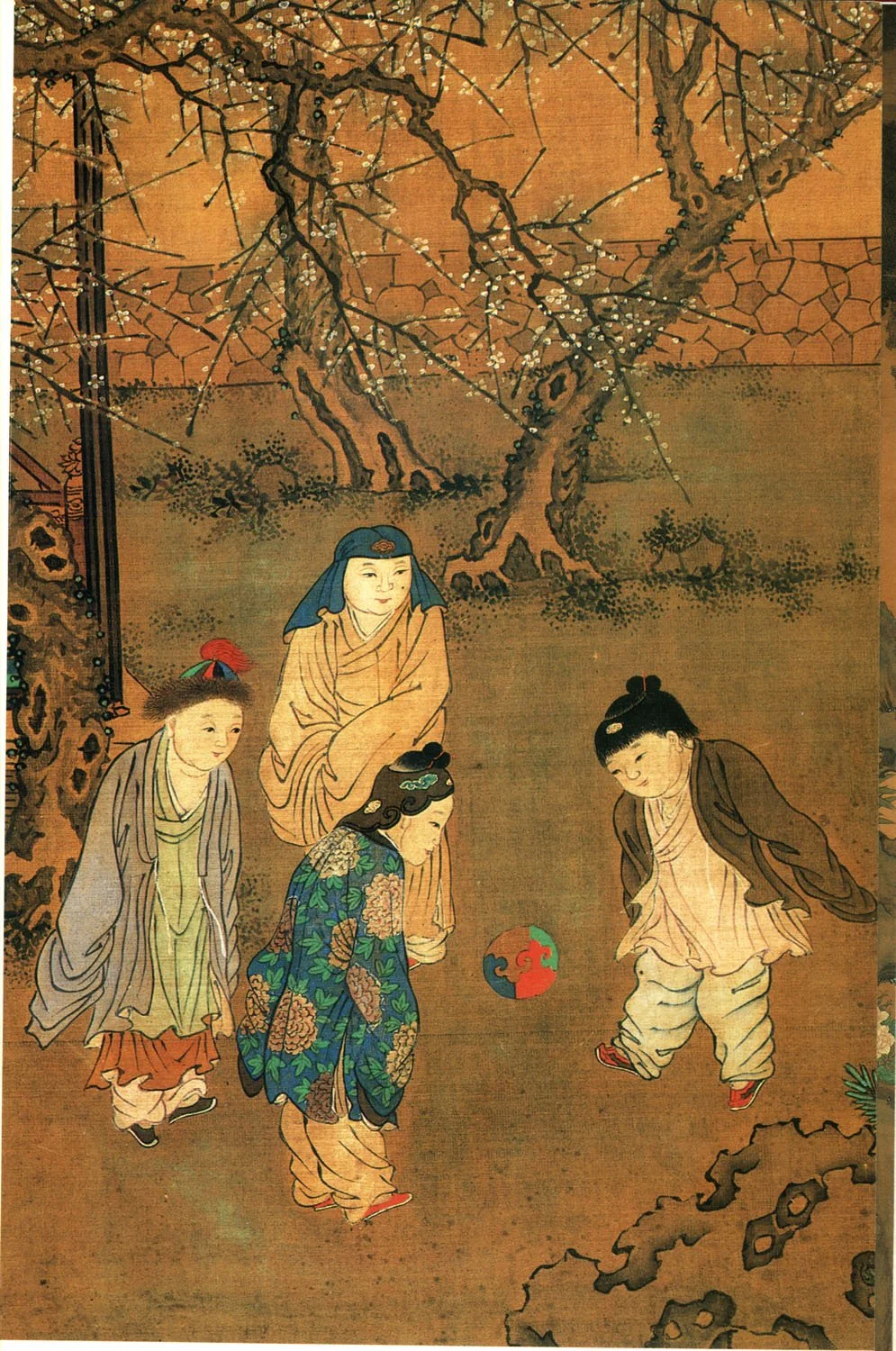

Song Emperor Taizu, Emperor Taizong, prime minister Zhao Pu and other ministers were playing Cuju.

circa 1300 AD, Yuan Dynasty

One of the oldest kicking games ever played originated in China and is called 蹴鞠 (cuju), meaning "kick-ball." The earliest versions of cuju date back over 2,000 years to the Han Dynasty (200 BC), and it remained popular until its eventual decline in the Ming Dynasty (1368 AD).

Because the game was played in various regions over thousands of years, rules and styles varied. Historians compare the game to a combination of modern-day volleyball, basketball, and soccer. The objective was to kick a ball through a net positioned on a pole high above half court (the fengliu yan) or into a goal at the far ends of the playing field. The match was won by the team or individual with the most goals.

Additionally, there were versions of cuju performed as entertainment or for celebrations and rituals. These versions often focused on intricate skills and movements, resembling martial arts demonstrations in some ways.

Amusements in the Xuande emperor’s palace (detail). Ming artist, approx. 1426-1487

One Hundred Children in the Long Spring. 12th century AD, Song Dynasty

Cuju may have originated as a military exercise, intended to promote physical fitness and cooperation among soldiers. Notably, men, women, and children from all socioeconomic classes played the sport.

As China flourished in the 10th century, everyone from commoners to the emperor himself participated. Cuju clubs, known as yuanshehui or qiyunshe, emerged among the leisure class. Popularity waned during the Ming Dynasty. Although it survived informally, the Honwu Emperor considered the game a distraction from work and military training, even imposing a temporary ban.

Thanks to artists and poets who documented the game's various forms and rules, researchers have been able to revive the tradition. Its legacy continues through cultural performances.

POWHATAN,

NARRAGANSETTS

& LENAPE

The earliest Western accounts of indigenous football in North America date back to the 1600s (although these games most definitely pre-date these accounts). These games were often played during social gatherings for harvests and hunting seasons. They served as a way for groups to bond, gamble, and for some to find potential marriage partners.

In modern-day Virginia, Englishman Henry Spelmen, who was held captive by the Powhatan tribe and eventually became an interpreter, described a kicking game similar to English football—with the distinction that the men never fight or pull one another down.

William Wood wrote about the kicking games of the Narragansetts in modern day Rhode Island. He described groups of men with painted faces playing the game, while children and women made music and sang songs of encouragement. The games were good-spirited and ended with a feast.

In late 18th-century Ohio, Westerners observed a game played by the Lenape. This unique variation featured teams of men and women, with women allowed to hold and run with the ball. Men could only use their feet and would attempt to tackle women to regain possession.

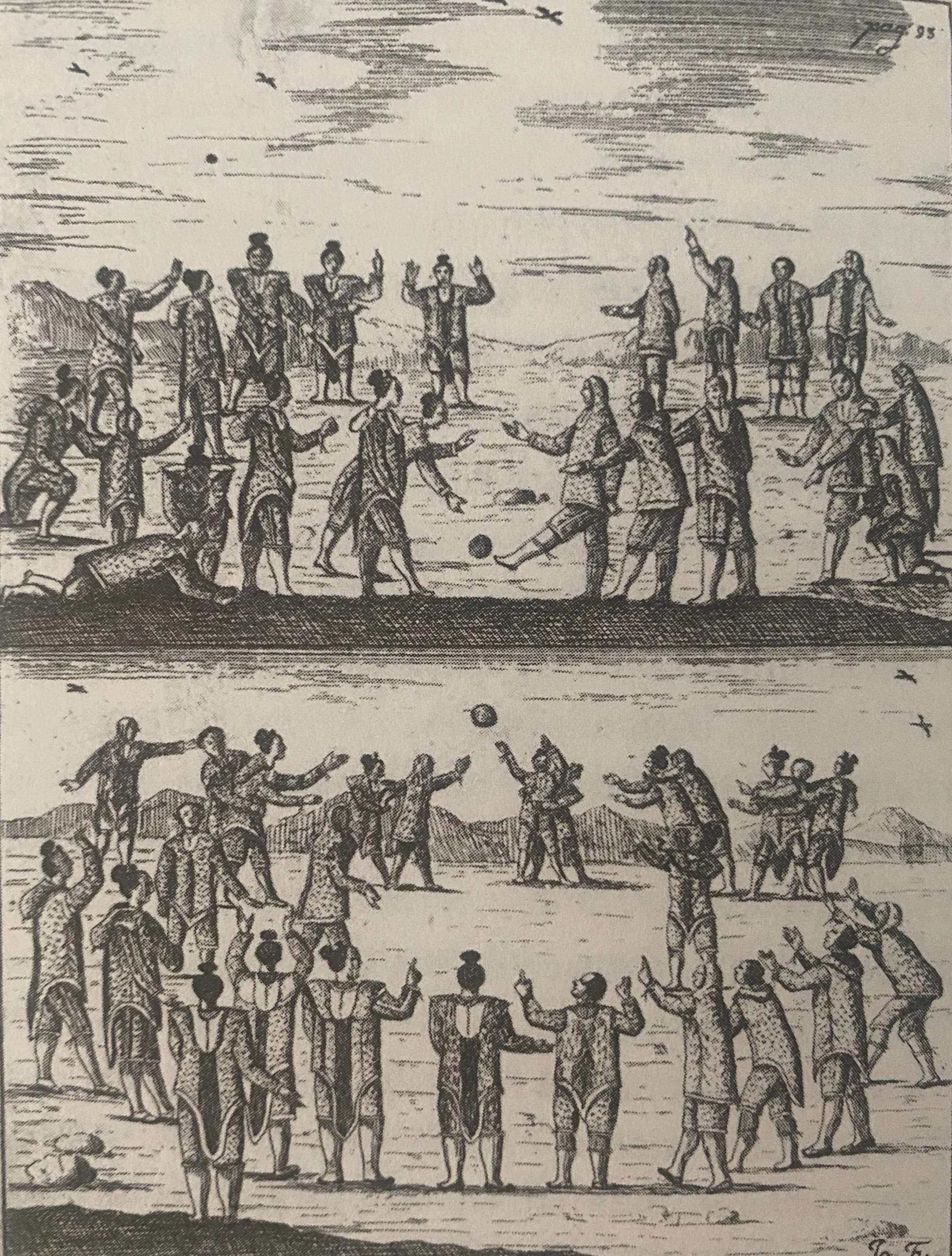

Inuits play ball games, at top, a sort of soccer or football, at bottom, a throwing game. Egede, Hans, 1686-1758. Kjøbehavn [Copenhagen]. Trykt hos Johan Cristoph Groth, boende paa Ulfelds-platz. 1741.

GREENLANDERS

Norwegian missionary Hans Egede traveled to western Greenland in 1720 and described a kicking game as the group’s “most popular diversion”. Two teams would face off on a long, open space. A goal was scored when players dribbled and kicked a leather ball to reach a barrier at the end of the pitch. Unlike other North American games, this game had a spiritual aspect. The Greenlanders believed that after death, souls would rise up above the earth and become football players (arastoq), who moved across the sky, appearing as the Northern Lights (asarnerit).

POK-TA-

POK

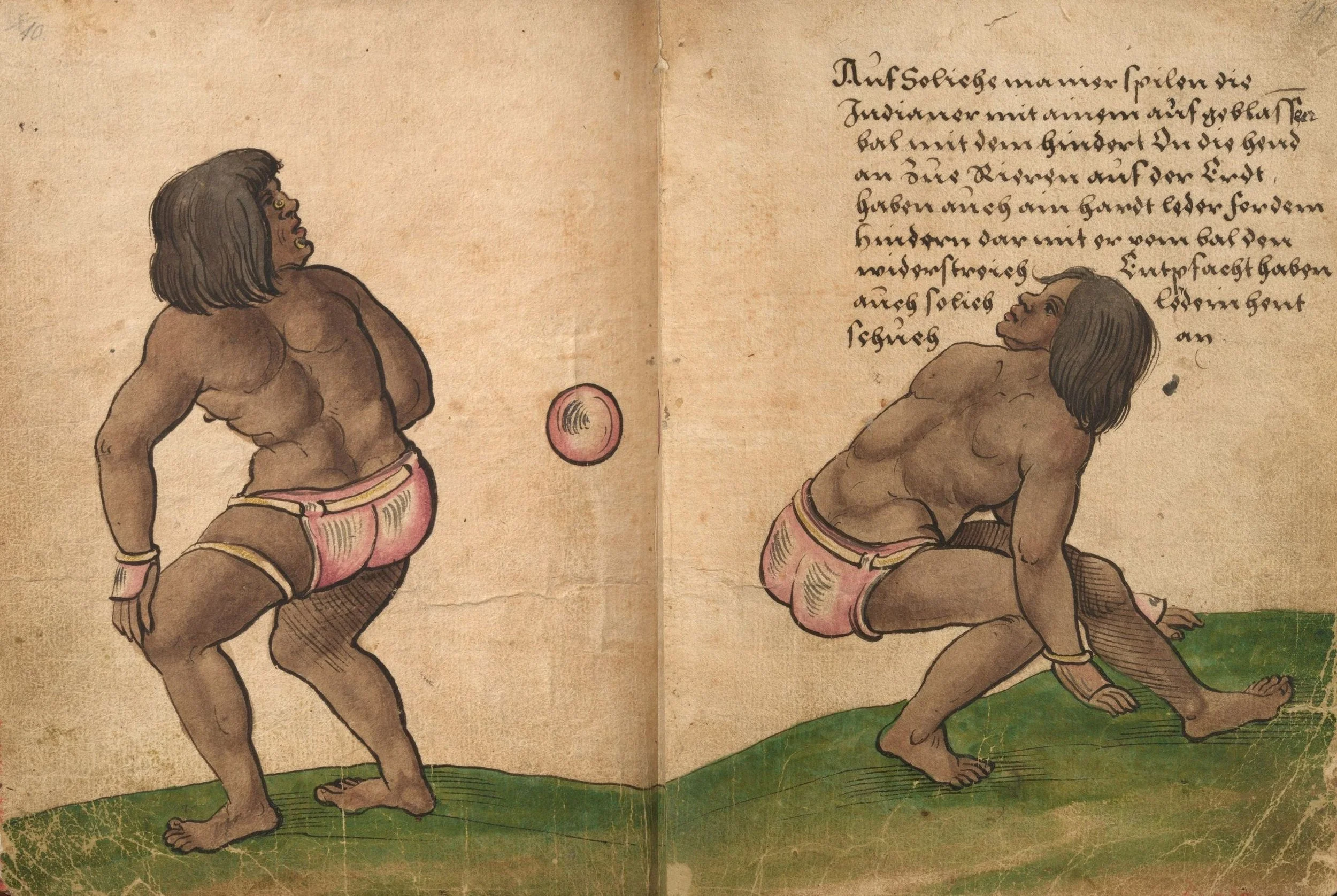

The earliest evidence of the meso-American pok-ta-pok dates back to around 600BC, and it remained popular until the 16th century. While related to football in its use of a ball and the goal of scoring, pok-ta-pok distinguished itself by requiring players to strike the ball with their hips rather than their feet. Instead of a leather ball, like in cuju or North American games, pok-ta-pok was played with a solid rubber ball that could weigh as much as 15 pounds.

Like cuju, hip-ball had military ties. Kings and noblemen used matches as a way to resolve disputes rather than resorting to battle. Goals were so difficult to score, games were often decided by other criteria. The game was so popular that recreational pok-ta-pok playing courts popped up in every city. Games could also be played in conjunction with religious ceremonies, and some accounts suggest that ritual sacrifices may have been performed in the pok-ta-pok court.

Ballplayer painting from the Tepantitla murals.

Pok-ta-pok court ruins

Aztec ullamaliztli players performing for Charles V in Spain, drawn by Christoph Weiditz in 1528.

Hip-ball carries spiritual significance because of its place in the Mayan creation story. Documented in the Popol Vuh, the Hero Twins are challenged to a game of hip-ball by the lords of the underworld—the game representing life and death itself.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 1500s, they considered pok-ta-pok to be an act of witchcraft and outlawed it. However, archaeological and historical research has revived interest in the game, leading to a cultural revival, particularly in regions with a strong Mayan heritage.